All Truth About Eidetic Memory – Case Closed

Table of Contents

Understanding Eidetic Memory

“Eidetic memory, sometimes called photographic memory, enables an individual to hold details of visuals or physical things. Retention and retrieval are almost perfect since this unusual cognitive phenomenon relies significantly on the visual cortex of the brain. In contrast to regular memory’s reliance on abstract remembrance, eidetic memory retains sensory elements with clarity. More efficient synapses and stronger brain connections in the visual pathways are believed to be the source of our remarkable memory for fine sensory data”.

How Does It Work

An amazing interplay of brain processes allows eidetic memory to work, which has been likened to having a mental image gallery. Picture your thoughts like a camera with an excellent lens. Unlike limited visual memories, this mental camera captures every nuance of the world around us as it unfolds.

At its core, this operation involves the visual cortex, the primary brain region responsible for visual information processing. This region acts like a high-definition screen, encoding every detail of the sensory input in those with eidetic encoding. This strong perception is further solidified by the memory’s file system, which is a complex network of connections between neurons. Such connections, called synapses, are efficient when it comes to storing and organizing data.

Increased brain connections and improved synaptic efficiency in visual pathways also aid in smooth recollection. Remembering anything is like having one’s brain recreate a high-definition image. By transforming fleeting events into strong, immutable memories, this incredible ability reveals the vast potential of the human mind.

The ghost and the science of eidetic imagery

While the scientists are debating some details of it – such as exactly how it works and what should be included in the definition – the main criteria are agreed upon since several decades back. And they are probably not what most people imagine them to be.

The most cited scientist in the field, Ralph Norman Haber, in 1979 summarized all the studies made up until that point on this elusive subject in a fascinating research paper titled “Twenty years of haunting eidetic imagery: where’s the ghost?”. This text was also commented upon by many of that time’s most proficient researchers on human psychology.

In his “ghost story”, Haber describes how his interest in eidetic imagery was piqued when he did experiments on so-called afterimages (a phenomenon entirely unrelated for eidetic memory, see the image below). He found some articles on people, especially children, who seemed to have a peculiar ability of still seeing an image in front of them after that image was removed.

Soon thereafter, Haber researched this himself and managed to quickly find dozens of children who seemed to have this so-called “eidetic” ability. They were not very common, but also not particularly rare. In Haber’s study, about 8 % of the tested children seemed to have been given this gift. That is about one kid in every small school class.

But before you conclude that one of your classmates in kindergarten saw the world very differently from yourself, let’s take a closer look at precisely what it was that these 8 % of children could do.

Haber’s experiment for testing eidetic memory was as follows: He would place the child in front of an easel where he then placed various pictures. At first, he just showed something simple, like a red square, and then removed it, asking the child to try and still see the square where it was before.

After this warm-up, Haber would place a more exciting picture, such as an illustration from a children’s book, on the easel. The child was asked to look at the picture (not staring at it but just freely let the eyes move) for 30 seconds, and then the picture was taken away.

After this, the child was asked if it could still see something where the picture had been. Most children said that they could not, but a few of them talked as if they again saw the picture standing on the easel and could describe parts of it. Here is an excerpt from a conversation with such a child (a 10-year-old boy) just after the image was taken away:

E: Do you see anything there?

S: I can see the cactus – it’s got three limbs, and I can see the Indian, he’s holding something in his hand, there’s a deer beside him on his right-hand side – it looks like it’s looking toward me and three birds in upper left-hand corner, one in right-hand corner, it’s larger and a rabbit jumping off the little hill.

E: Can you tell me about the Indian – can you tell me about his feathers, how many are there?

S: Three or two.

E: Can you tell me about the feet of the deer?

S: They’re small.

E: Are they all on the ground?

S: No.

E: Can you tell which ones aren’t?

S: One of the front ones isn’t.

E: Tell me if it fades.

S: I can still see the birds and the Indian. I can’t see the rabbit anymore, (pause). Now it’s all gone.

From these experiments, Haber and his colleagues came up with a few criteria to identify if a child had an eidetic memory or not. First of all, the child should see the image in the same colors as it had originally (that is, not in inverted colors like the ones you saw if you tried the AFTERIMAGE experiment above). The image should also not move when the child moved his eyes, but he should be able to look at it and talk about it as if it was still physically there on the easel. Haber also noticed that the image always went away after a small period, at most four minutes.

And that was it! Those were the only criteria! Of course, Haber and many others initially also wanted to add that the children should be able to describe the images in superior detail compared to the children who were not eidetikers, but after much experimentation, this criterion had to be abandoned.

Eidetic children didn’t actually remember significantly more of what was in the image during the minutes that their eidetic image lasted. They could tell just as much, or as little, about it as their non-eidetic friends. This detail, however, has managed to escape almost every internet article writer to date, significantly contributing to the myth we are about to debunk next.

Eidetic vs. Photographic memory?

Hearing about someone being able to see a non-existing image as if it really was in the room implies that this person’s mind has somehow recorded, or photographed, this image and saved it in that person’s neural network (i. e. brain). But the more the eidetic children were studied, the more apparent it became that this was not the case.

Ulric Neisser, one of the researchers, commenting on Haber’s scientific summary, describes an experiment of a 12-year-old girl with seemingly powerful eidetic abilities. She was asked to slide her eidetic picture of an elephant down to a blank sheet of paper and then trace its outlines with a pencil.

The girl had already done a tracing with a real picture of an elephant under the paper (as when ordinary people would trace something), so it was clear that she could, in this way, produce a realistic looking elephant.

When faced with this task, she was delighted to do it (and claimed that she could clearly see her eidetic image). Surprisingly she ended up drawing something resembling a cartoon elephant, or such an elephant as children would usually draw when asked to do so.

This seemed to confirm that the eidetic image that she could see was not at all like a photograph, but rather, like any other memory, a reconstruction made by the brain based on reality, other memories and preconceptions.

This is how the brain normally operates and seems to be what happens in eidetic minds too. Eidetic children made the same errors as everyone else. They misremembered things, their brains sometimes added stuff to the pictures that weren’t there, and it happened that they changed their mind about what they saw.

The only thing separating eidetikers from non-eidetikers seemed to be the subjective experience of seeing the picture still in its place compared to just recalling details about it from memory. So much for this alleged super-human ability.

But to some scientists, this was very unsatisfactory. Was this really all there was to it? Caught by the idea of the perfect, photographic memory that the experiences of the eidetikers initially had appeared to be offering, a couple of researchers devised a fool-proof test that would objectively find out if photographic memory existed once and for all.

The Ultimate Eidetic Memory Test

On the internet, it’s easy to find tests that claim to prove that you have a photographic memory (or eidetic for that sake, but when they write “eidetic” – photographic is almost always what they mean). Most of them are, of course, completely unscientific, with titles such as “only 1 percent of the population can pass this photographic memory test” (although judging from the comments that figure should be adjusted to about 90 %…).

Buzzfeed provides a test that “is impossible unless you have a photographic memory,” but that can easily be beaten if you’ve practiced memory techniques.

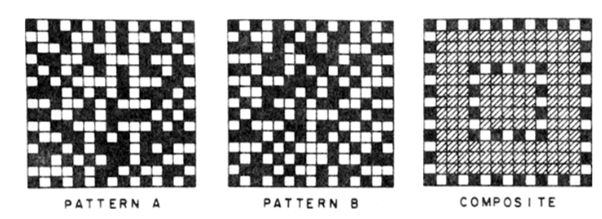

There is, however, one test also available online that not only the internet but even science has used for determining the photographic quality of someone’s memory. It is called the composite image test and was devised by Kent Gummerman and Cynthia Gray in a quest for finding an objective eidetiker.

The basic idea went like this: If you genuinely have a photographic memory, or a “perfect” (realistic) eidetic memory, you should be able to remember also very complex and meaningless pictures, right? Say a random grid of black and white squares.

And if you have the ability of actually keeping on seeing this picture when it’s gone, you should also be able to visualize that on top of a new, similar-looking image, in order to create a combined image which would reveal some “secret” combined symbol. That would be impossible to guess from just seeing one of the two images separately.

Here is an example of such a test used by Gummerman and Gray:

They tried 270 subjects (mostly children but also many adults). Out of these, only two fulfilled Haber’s “subjective” criteria for having an eidetic memory. None of them passed the composite image test.

But well, this was only 270 subjects, and since just two of them were eidetic, there was still a chance that a super-eidetiker would emerge from a larger population sample.

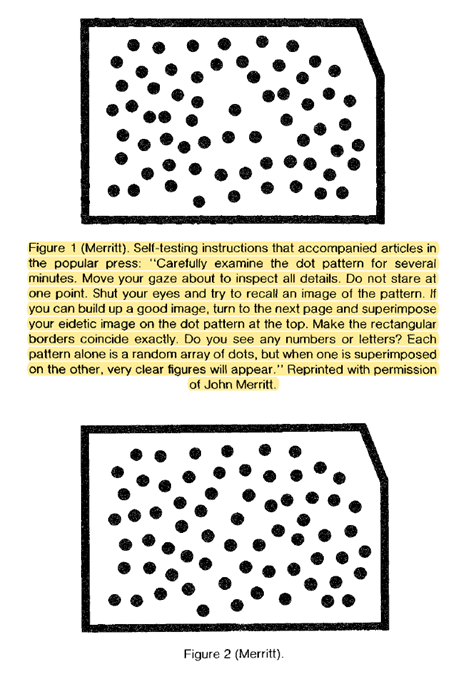

Here is where John O. Merritt at Harvard University comes into the picture. This idea and the curious case of Elizabeth (the only confirmed but extremely questionable subject with photographic memory EVER, read about it in our article on photographic memory) made Merritt publish several articles in big American newspapers during a period of many years, containing a small test very similar to the one above.

Instead of squares, Merritt used random dots. Here is his version, as given in the papers:

Merritt himself estimates that the test reached millions of people throughout the years. Out of them, only 30 ever contacted him, and none of those could pass a similar test when he met them in person.

Eidetic memory vs. Hyperthymesia?

Maybe you find it hard to accept that the 100 % perfect memory doesn’t exist. After all, you have seen it so many times in movies, read about it in (not so well-researched) articles, and maybe even remember seeing a documentary or two about people with total recall.

If the latter is the case, it is likely that those documentaries were about people with hyperthymesia, or Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) and that parts of your memory fails you.

Hyperthymesia is a recently (in 2006) discovered condition in which a person remembers much more from his or her life than a regular person. In contrast to eidetic memory, hyperthymesia is extremely rare. There are only some dozens of confirmed cases all over the world.

When you hear these exceptional persons talking about what they ate for breakfast on April the 4th 1998, or what the weather was like November the 18th ten years ago, it’s easy to get carried away. Many writers and tv producers have – a bit too quickly – jumped to the conclusion that someone with hyperthymesia “remembers every little detail that has ever happened to them” (open virtually any article on the subject, and you’ll see some version of this).

This is far from reality. No-one with hyperthymesia has ever claimed to remember everything. When they discovered Jill Price, the first confirmed person with this condition, the scientists at first guessed that she would be extremely intelligent and have an extraordinary general memory. But tests soon revealed her IQ to be 95 (just below average) and her ability to memorize random information, or facts for exams, to be no better than that in just any person. This seems to hold for all of the HSAM subjects.

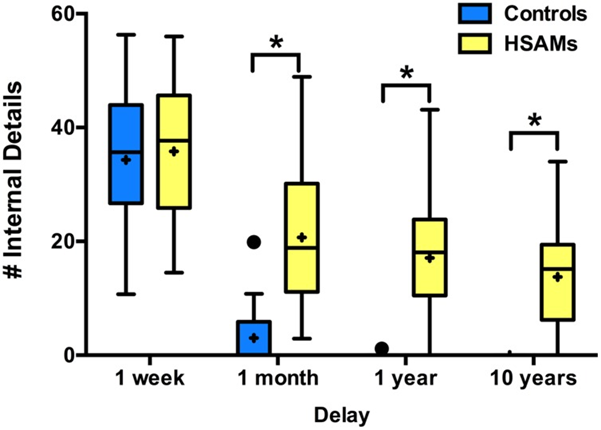

They do have a fantastic autobiographical memory, but at a closer look, it appears as if they don’t remember more about their lives than the rest of us to begin with, it’s just that they remember it for a more extended period of time. When scientists compared the memories of a group of HSAMs with a “normal” control group, they found that both groups remembered what had happened to them the last week in approximately the same detail. It was first when you looked further back in their memories that the HSAMs were superior. Their retention of the memories was far better.

An HSAM subject will remember what happened to her ten years ago, but she will not remember it better than you remember what happened to you last week. It is still inspiring, of course, but quite different from the idea you get about it from careless media reports.

James McGaugh, the scientist who “discovered” Jill Price, expressed it like this: “She doesn’t remember everything; what she remembers she doesn’t forget, that’s the difference.”

Eidetiker who draws tremendous cityscapes from memory

There are countless examples of people with good memories out there. These good memories are often mistaken for being photographic, usually for no other reason than that this is the easiest way to describe a very detailed recollection of information.

Some deserve this attribute more than others. I feel that I have to mention Stephen Wiltshire here, a British autistic savant who has trouble keeping an ordinary conversation but can draw tremendous cityscapes from memory after just having looked at them for 30 minutes or so in a helicopter. What he does is stunning, but the careful eye will notice that even the mental pictures of this great mind are not really photographic. The overall image is very close to the real deal, but even Wiltshire’s brain leaves out some details, adds others, and mixes some around. Yet his memory works in a reconstructive way.

And he should probably be thankful for that. Our beautiful, non-perfect perception and memory ability is what makes us human. To cite the Argentinian novelist Jorge Luis Borges: “To think is to forget differences, generalize, make abstractions.” Without this ability, the world would make absolutely no sense to us, even if we then would be able to remember every minute detail of it.

Our ability to forget appears very closely related to our capabilities to have abstract thoughts and functioning in a society. Something clearly illustrated by the high number of autistic savants who, by chance, have had to sacrifice higher-level mental abilities for low-level, item-specific ones such as a fantastic memory for a particular type of information.

Perhaps we always have to sacrifice something?

How to get an eidetic memory!

It is quite likely that you started reading this article in the hopes of acquiring an eidetic memory yourself. I wonder if you feel as tempted now.

After realizing the true nature of this scientific term – a subjective experience that lasts for a few minutes and doesn’t really make you remember more details anyway – you may be inclined to agree with one of the more belittling peer comments on Haber’s original article on his haunting ghost: “Haber may be left with a ghost, but he has reduced it to a rather insignificant one that requires easels, 30-second exposures, and prior afterimage training, and is neither help nor hindrance. Such a ghost we can live with and study in a more leisurely way.”

Also, having realized that the only way of getting a more “photographic-like” memory would likely be giving up parts of your most important and constructive mental generalization powers, you perhaps don’t feel so attracted to the idea of a photographic memory anymore either.

Personally, I would recommend the less drastic but still tremendously powerful memory techniques that have been developed for thousands of years to make normally functioning brains remember much better. They’re not photographic, but they can make significant parts of your life a lot easier without at the same time making other parts harder. A rare win-win in the realms of the mind.

If, however, you still really, really want a photographic memory – if you really, really want to be able to store snapshots of your life in perfect detail and to see them in front of you without distortion even years from now – only for you I will share one almost certain method for achieving this.

1. Look carefully at whatever you want to remember.

2. Make sure that you are facing it and that nothing blocks your sight.

3. Pick up your smartphone and take a picture.

This will work to 100 %.

Unless, of course, you forget where you put your phone…